Roland Barthes (1915-1980) was a French philosopher and literary theorist, he was not a photographer. This book deals with the question: what is a photograph? from that perspective.

Barthes describes the essence of photography as distinct from both art and history.

Art, he contests, is the result of a creative process undertaken by an artist; whereas a photograph is primarily the preservation of “something that was”.

History is a perspective on past events; always open to challenge and contradiction. A photograph, by contrast, is undeniably “something that was”, and it is up to the viewer to infer meaning. A meaning which, as I show below, may change from person to person or evolve over time.

The photographer, and the subject, if it is a person aware of being photographed, can suggest an implied meaning. However, without knowledge of this intent, the viewer may see the image differently, and derive a meaning entirely personal to them.

Tim Flack’s fine book on horse photography, ‘Equus’, ends with this quote from Barthes’ book: “Ultimately a photograph looks like anyone except the person it represents.”

Scope & Objective of this Post

Barthes is only interested in documentary photography. To him the essence of photography is the fact that it occurred and can only occur once. He has no truck with landscapes, portraits, still life, nudes, or any other form of art photography. So one might validly ask why this is relevant to a blog on learning the art of photography? It’s just that I stumbled across several references to this book from respected sources, that I felt compelled to buy and read it. Then to explain why I think it is relevant to this project and blog.

So everything I currently know, or can opine, about the philosophy of art is written in the following sections:

- Philosophical Context (Literary Theory): Structuralism and Post-Structuralism

- Concurrent Art Movements: Modernism & Post-Modernism

- Barthes’ Death of the Author

- Why any of the above matters to a photographer.

- Footnote: Why was the book called “Camera Lucida”? and other musings

Philosophical Context (Literary Theory): Structuralism and Post-Structuralism

Literary Criticism Pre-Structuralism – Philosophy of Language

Pre-structuralism the prevailing view was that each word related to a specific thing or “form” as defined by Plato. The meaning of each word related directly to the form in the real world. Ideas and concepts (like being angry) were also forms, on an equal footing linguistically with tangible objects such as trees and chairs.

This all seems fairly obvious and is the way we seem to use language all the time, e.g., when somebody says “tree” or “angry” we know what they mean because we know what that form is in the real world.

Advent of Structuralism

However, in the 1940s, Ferdinand de Saussure led an intellectual movement that held that words only had meaning in relation to other words. For example, we know what “tree” means because we know what “plant” means and “tree” is a type of “plant” and larger than a “shrub”. Apologies to any botanists for the simplification.

So, a language is a structure of words relating to other words in a commonly agreed manner. The “commonly agreed manner” may evolve over time and relies on influential past usage of the language.

Therefore, a literary text is a list of words and punctuation, whose meaning is influenced by both the author and the canon of texts that precede it.

More broadly, structuralism holds that any art work is entirely understood as the combination of:

- the intent of the artist

- the cultural context surrounding the artist at the time.

In Photography the following terms are all fundamentally structuralist:

- “photographic genre” implies rules and tropes specific to each genre. The rules standardise a work into a familiar structure whilst the tropes are a shorthand to meaning. Tropes in street photography include:

- showing only legs in a crowd scene

- use of slow shutter speed to emphasise movement

- “telling a story” often relies on tropes as shorthand

- “artistic vision” is the intent of the author.

In summary, structuralism holds that any meaning inferred about a work, other than that intended by the author, is simply wrong.

Post-Structuralism

Post-structuralism refutes my previous statement, and holds that understanding authorial intent and all cultural references, is both impossible and undesirable. Instead, it is the role of the art consumer to interpret and infer meaning. A meaning personal to them.

Therefore, a piece of art may:

- be validly interpreted differently by different people

- have a meaning that changes over time as cultural norms change.

Barthes’ 1977 essay: “From Work to Text”, defines work as a creator centric view of art, whereas a cultural text (any art including a novel, painting, photograph, play or conceptual installation) is the consumer centric reference to the same thing.

The key thing: who determines what something means, author or reader?

Concurrent Art Movements: Modernism & Post-Modernism

Modernism, roughly 1900-1950

“Modern” means new and better. “Modern art” embraces all the new styles, all the “..isms”, e.g., cubism, surrealism, fauvism, etc.

In Europe at least, dominant influences on the visual arts at the start of the 20th century included:

- the threat of photography as a cheap, easy and increasingly popular alternative to painting’s core market of portraiture, landscapes and general fine art

- psychoanalysis and the theories of Sigmund Freud including the role of the sub-conscious mind, and spirituality

- the rise of the art collector as an alternative benefactor to aristocracy and the church.

The creative response to the above is greater artistic freedom, and the rise of non-objective or abstract art in its various guises.

Post-modernism, following WW II

As post-structuralism denies the absolute certainty of structuralism, post-modernism refutes the metatext and claims of modernism for the visual arts. Specifically, that it is always a better way of expression, and that meaning is exclusively determined by the intention of the author.

Again the emphasis moves from the art creator to the art consumer, with the expectation that the consumer has to bring their own emotional response to the art.

Mark Rothko famously said: “A painting is not a picture of an experience, but is the experience.”

Right:

Mark Rothko

Light Red Over Black

1957

Barthes’ Death of the Author

Roland Barthes 1967 essay, is considered to be the bridge that extends structuralism into post-structuralism. Following its creation a text may be interpreted differently by those viewing or reading it.

Art produced by an artist of great sensitivity but lacking in education may later be intellectualised and given meaning by the art world.

So is the death of the author, the birth of the reader? Many people (mainly authors) refuse to accept that the interpretation inferred by a reader, lacking in cultural sensitivity, has the same validity as that ascribed by the author.

Why Any of the Above Matters to a Photographer

The art world of photography is dominated by structuralist concepts, salons and distinction bodies:

- separate work by genre

- require a series of work to support a written statement of intent

- encourage the use of tropes to make an image easier to understand.

Barthes posits that a photograph may connect with great impact with someone for reasons that are unrelated to the general message (its “stadium”), which is available equally to all viewers to infer. A detail (its “punctum”) may confer a highly subjective meaning for that viewer, whilst having been possibly, entirely overlooked by the author.

By definition, there is nothing a photographer can do to create an image with a greater punctum. By the time the image is made, it exists as a cultural text, independent of authorial intent. Some humility is required to appreciate that it may be interpreted in different ways from that intended.

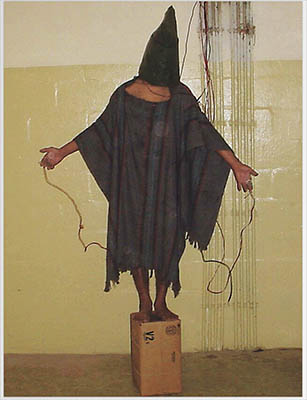

“The Hooded Man”, left, by Sergeant Ivan Frederick, is considered by Time Magazine as one of The Most Influential Images of All Time.

One of thousands taken by US soldiers serving in Abu Ghraib prison, Baghdad. The authorial intent was almost certainly one of trophy collection.

However, in the cultural context of the civilian western world, the image is of the war crimes and human rights abuses perpetrated in our name.

To a former detainee, the punctum may be aspects of the image that gives clues to the subject’s pain, his identity or the identity of his abusers. The meaning will be personal to the viewer.

The above is an extreme example of meaning changing with cultural context.

Footnote: Why the book is called “Camera Lucida” and other musings

The term “Camera Lucida” differentiates the role of the camera in photography (as an instrument to record a moment in time), from that of the Camera Obscura, as an instrument used by painters to make art.

The somewhat pretentious term, “author”, that competition judges use instead of “photographer”, makes a whole lot more sense when the photo is deemed a cultural text.